Biology of the dark rover ant

The dark rover ant (DRA), Brachymyrmex patagonicus, is a small invasive ant species that has become increasingly common in parts of California. First detected in the state in 2010 (Martinez et al. 2011), it is now found across Southern California and parts of the lower Central Valley (Taravati 2018).

This is a relatively small ant, with workers measuring just 1–2 mm (1/32 to 1/16 inch) in length—significantly smaller than Argentine ant (Linepithema humile) workers, which range from 2.2 to 3.2 mm (1/16 to 3/32 inch). Despite their small size, these ants can become a nuisance indoors and may be difficult to control using products formulated for more common ants, such as Argentine ants. Although they are not known to sting or bite, the dark rover ant’s nuisance behavior indoors and expanding range make it a species of interest for pest control and urban entomology professionals.

Identification

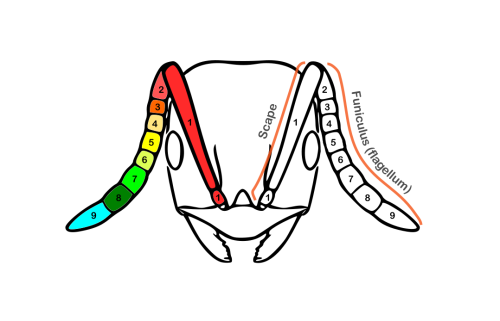

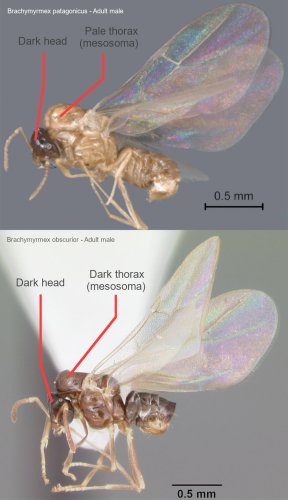

The genus Brachymyrmex can be identified by its distinctive 9-segmented antennae (Fig. 1), a unique morphological feature that is exclusive to members of this genus. Additionally, B. patagonicus, or DRA, can be identified by the presence of robust, erect hairs on their thorax and abdomen (gaster). DRAs are darker in color than B. depilis (Fig. 2). Male DRAs are bicolored, with a dark brown head and gaster, and the rest of the body is pale yellowish-brown (MacGown 2008) (Fig. 3). Another very similar species is the obscure rover ant, B. obscurior (Fig. 2), which has a dark body color but has smaller eyes and denser pubescence, especially on the gaster (MacGown 2009).

Origin and distribution

Native to South America, B. patagonicus has spread throughout the southern United States and is considered an invasive pest. It has been found in South America in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela; In Central America in Costa Rica, Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico (Ortiz-Sepulveda et al. 2019). It was reported from Hong Kong in 2018 (Guénard 2018), and it is also reported from Kobe city in central Japan (Ortiz-Sepulveda et al. 2019), although its establishment in Japan is yet to be determined (Guénard 2018). Edward O. Wilson, as cited in MacGown (2008), noted that the species had been present in the United States since the 1950s. However, the first official report was not published until decades later, documenting a 1976 collection from Madisonville, Louisiana (Wheeler and Wheeler 1978). Since then, the dark rover ant (DRA) has spread to numerous U.S. states, including Florida, Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina, North Carolina, Mississippi, and Tennessee (Hill 2017); Arkansas (MacGown et al. 2007); as well as Texas, Arizona, and California (Martinez et al. 2011). Since its introduction to California, the DRA has spread to many areas of Los Angeles, Riverside, Orange, San Diego, and Kern Counties. Currently, DRA is one of the most commonly sighted ants in many urban parks as well as residential and commercial neighborhoods in Southern California (unpublished data). It was detected for the first time in Europe in 2016 in Almeria, Spain (Espadaler and Pradera 2016), and has expanded its range into other parts of the country such as Carboneras and Agua Amarga (Reyes-López 2018), Mairena del Alcor (Cipollone-Pérez et al. 2023), Calahonda, Elche (Pradera and Espadaler 2024), and other areas on the coastal Mediterranean and Alboran seas and the North Atlantic ocean (Pradera and Espadaler 2024) from Cádiz (Reyes-López et al. 2024) to Alicante, in an area stretching over 730 km on the coast (Fig. 4) . DRA was sighted in the Netherlands but it didn't seem to have established there (Boer and Vierbergen 2008).

Foraging

These ants form loose (Keefer 2016), low-density foraging trails (unpublished data), unlike those of Argentine ants and red imported fire ants. Foragers follow trails as isolated individuals, or groups of two to ten or more ants. There can be large gaps between the foraging groups on trails (unpublished data). In a laboratory study, DRA workers, queens, and brood moved to a satellite nest to be in closer proximity to the food source, a typical behavior of tramp ants (Keefer 2016).

Aggression toward other ants

Dark rover ants show and receive little or no aggression in interactions with Argentine ants and red imported fire ants (RIFA). DRAs are commonly found in areas dominated by the red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) and Argentine ants (MacGown et al. 2007, Martinez et al. 2011). In some cases, they have even been observed co-foraging alongside RIFA, Argentine ants, and Asian needle ants (Brachyponera chinensis) (Bowers 2018). Also, unlike the anecdotal claims about the increase of DRA activity in areas where RIFA was suppressed (Dash 2004), the suppression of RIFA did not significantly increase the abundance of DRAs in pitfall traps in a study in South Carolina (Bowers 2018).

However, among their own species, dark rover ants display fierce aggression toward members of other conspecific colonies. This high level of intraspecific aggression contrasts sharply with the cooperative behavior of Argentine ants and polygyne RIFA, both of which form expansive, multi-queen supercolonies with minimal conflicts among conspecific colonies.

Nest

DRAs nest in soil, inside loose plant material such as under tree bark, under mulch and outdoor objects, and indoors. Locating nests in soil is difficult because of the small entry hole (Bowers 2018) and low-density foraging trails that usually help lead an observer to the nest entrance (unpublished data). Most DRA colonies are comprised of a single nest with a single queen (Eyer et al. 2020). This nest structure is in sharp contrast with the nest structure of other common invasive ant species such as the Argentine ant and RIFA, which form interconnected nests containing numerous queens while showing no aggression toward non-nestmates (Eyer et al. 2020). Nests can be found in high densities in areas dominated by DRAs with separate colonies located within a few centimeters of each other. Occasionally, nests can be found indoors inside kitchens and bathrooms (MacGown et al. 2007).

Diet

DRA are omnivores and are known to feed on sweet food such as honeydew (Dash 2004), sucrose (Miguelena and Baker 2014), and dead arthropods (Unpublished data). They readily feed on sugar-based gel baits and commercial liquid ant food (unpublished data). In a laboratory trial, DRA ants preferred honey spread and pancake syrup over sunflower oil, shrimp sauce, pineapple preserves, sunsweet butter and oil, apple butter, sesame seed oil, and sweet and sour sauce. In field food preference trials, DRAs switched between carbohydrates and proteins at different times of the year, feeding more on tuna during summer and fall and more on pineapple preserve and honey spread during winter and spring (Keefer 2016).

References

Boer P, Vierbergen B. 2008. Exotic ants in the Netherlands (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomol. Ber. 68(4):121–129.

Bowers DQ. 2018. An Investigation of the Distribution and Behavior of the Dark Rover Ant, Brachymyrmex patagonicus Mayr, in South Carolina [Master’s Thesis]. Clemson University. [accessed 2024 Oct 16]. https://search.proquest.com/openview/7c645c22059c7794fb25a38510f4185f/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

Cipollone-Pérez A, Alarcón P, VIDAL-CORDERO JM. 2023. Primera cita de la especie alóctona Brachymyrmex patagonicus Mayr, 1868 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para la provincia de Sevilla (España). Bol. Soc. Andal. Entomol. 33:190–195.

Dash ST. 2004. Species diversity and biogeography of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Louisiana with notes on their ecology. Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College. [accessed 2025 Feb 2]. https://search.proquest.com/openview/7ac64210362ea32c0d1e7e1d4ebf35c3/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

Espadaler X, Pradera C. 2016. Brachymyrmex patagonicus Mayr, 1868 y Pheidole megacephala (Fabricius, 1793), dos nuevas adiciones a las hormigas exóticas en España. Iberomyrmex. 8:4–10.

Eyer P-A, Espinoza EM, Blumenfeld AJ, et al. 2020. The underdog invader: Breeding system and colony genetic structure of the dark rover ant (Brachymyrmex patagonicus Mayr). Ecol. Evol. 10(1):493–505. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.5917

Fisher BL, Cover SP. 2007. Ants of North America: a guide to the genera. Univ of California Press. [accessed 2025 July 28]. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=nO3hnw8vDRIC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=ants+fisher&ots=Dvvmre1psr&sig=xuXrFxTEngVc5uQsPgKAZsbpYVQ.

Guénard B. 2018. First record of the emerging global pest Brachymyrmex patagonicus Mayr 1868 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) from continental Asia. Asian Myrmecol. 10:e010012.

Hill JG. 2017. First Report of the Dark Rover Ant, Brachymyrmex patagonicus Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), from Tennessee. Trans. Am. Entomol. Soc. 143(2):517–520. https://doi.org/10.3157/061.143.0218

Keefer TC. 2016. Biology, Diet Preferences, and Control of the Dark Rover Ant Brachymyrmex Patagonicus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Texas. [accessed 2024 Oct 14]. https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/157072.

MacGown JA. 2008. Brachymyrmex patagonicus Mayr 1868. [accessed 2025 July 25]. https://mississippientomologicalmuseum.org.msstate.edu//Researchtaxapages/Formicidaepages/genericpages/Brachymyrmex.patagonicus.htm#literature.

MacGown JA. 2009. Brachymyrmex obscurior Forel. [accessed 2025 July 28]. https://mississippientomologicalmuseum.org.msstate.edu/Researchtaxapages/Formicidaepages/genericpages/Brachymyrmex.obscurior.htm.

MacGown JA, Hill JG, Deyrup MA. 2007. Brachymyrmex patagonicus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), an emerging pest species in the southeastern United States. Fla. Entomol. 90(3):457–464.

Martinez MJ, Wrenn WJ, Tilzer A, et al. 2011. New records for the exotic ants Brachymyrmex patagonicus Mayr and Pheidole moerens Wheeler (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in California. Pan-Pac. Entomol. 87(1):47–50.

Miguelena JG, Baker PB. 2014. Evaluation of liquid and bait insecticides against the dark rover ant (Brachymyrmex patagonicus). Insects. 5(4):832–848.

Ortiz-Sepulveda CM, Van Bocxlaer B, Meneses AD, et al. 2019. Molecular and morphological recognition of species boundaries in the neglected ant genus Brachymyrmex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): toward a taxonomic revision. Org. Divers. Evol. 19(3):447–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13127-019-00406-2

Pradera C, Espadler X. 2024. Nuevas citas sobre la presencia de hormiga exótica Brachymyrmex patagonicus Mayr, 1868 (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) en España. Bol. Asoc. Esp. Entomol. 48. [accessed 2025 July 23]. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=02108984&asa=N&AN=182490760&h=7nrgR6IhXjmoZKUUEn%2BLJKBrm2lFsVXmPCjnkLpGGXDpHX4IG0B8qrmDtzyoG9bqg4OMbtqBJUFU9riR0HYAmw%3D%3D&crl=c.

Reyes-López JL. 2018. Nuevos datos sobre la presencia de Brachymyrmex patagonicus Mayr, 1868 (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) en Almería (Andalucía, España). Bol. SAE.(28):140–142.

Reyes-López JL, RODRÍGUEZ-REYES M, ANDREU MG, et al. 2024. Nueva cita de Brachymyrmex patagonicus Mayr, 1868 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) en la península ibérica: ahora Cádiz (Andalucía, Sur de España). Bol. Soc. Andal. Entomol. 34. [accessed 2025 July 23]. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Joaquin-Luis-Reyes-Lopez/publication/381773064NuevacitadeBrachymyrmexpatagonicusMayr1868HymenopteraFormicidaeenlapeninsulaibericaahoraCadizAndaluciaSurde_Espana/links/667e5a84f3b61c4e2c94a7fe/Nueva-cita-de-Brachymyrmex-patagonicus-Mayr-1868-Hymenoptera-Formicidae-en-la-peninsula-iberica-ahora-Cadiz-Andalucia-Sur-de-Espana.pdf.

Taravati S. 2018. Dark Rover Ant: Current Status in California. UC IPM Green Bull. 8(2). https://ucanr.edu/blog/pests-urban-landscape/article/dark-rover-ant-current-status-california.

Wheeler GC, Wheeler J. 1978. Brachymyrmex musculus, a new ant in the United States. [accessed 2025 Feb 2]. https://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=PASCALZOOLINEINRA7950600730.